Santa Clara

$ 275

lksc1k051

2 koshare children are playing on a turtle figure with rock art and geometric designs

3.25 in H by 2.5 in W by 4 in L

Condition: Excellent

Signature: Stephanie Naranjo

Tell me more! Buy this piece!

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Stephanie Naranjo

Santa Clara

Stephanie Naranjo was born to Pauline Gutierrez and Frank Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo in 1960. Her maternal grandparents were Luther Gutierrez and Lupita Naranjo. She was born into a pottery making household and she showed interest early in life, making her first little figures around the age of eight. Some of her work was included in 1974s Seven Families in Pueblo Pottery exhibit at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

For most of her career Stephanie made polychrome bowls, koshare storytellers and pig figures. Back in 1974 her grandfather Luther was mostly collaborating with his sister Margaret. When Luther died in 1987, Margaret started working with his daughter Pauline. About a year later Pauline died and Margaret started working with Stephanie. Then Margaret passed on in 2018.

Santa Clara Pueblo

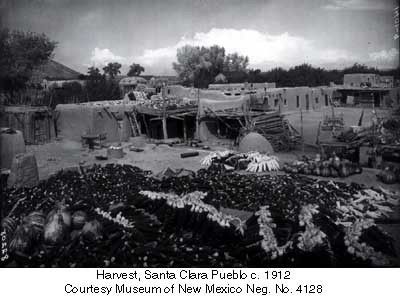

Ruins at Puye Cliffs, Santa Clara Pueblo

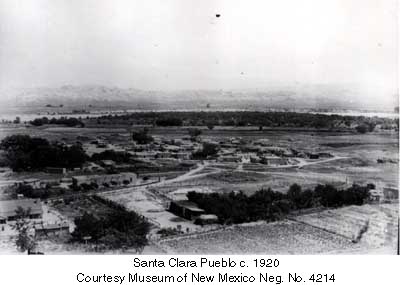

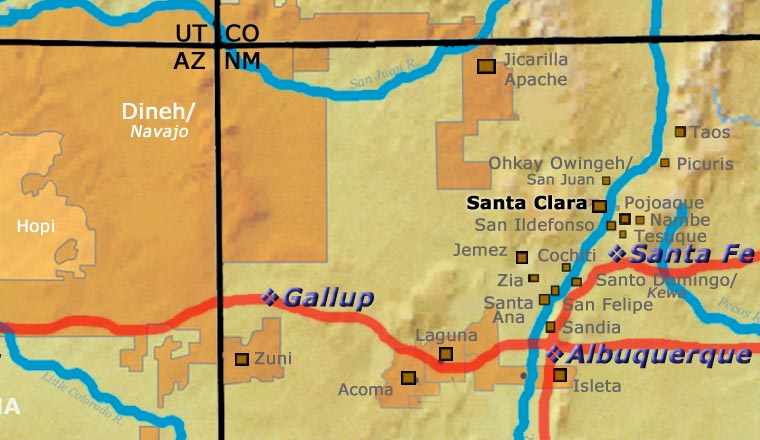

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to the pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 to about 1475. Drought then again forced the people to move, some of them going to the area of Puye (on the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains) and others to Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo, along the Rio Grande). Beginning around 1580, drought forced the residents of the Puye area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande and they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo on the west bank of the river, between San Juan and San Ildefonso Pueblos.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunque (the seat of Spanish government near San Juan Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders. When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso). An extended siege didn't subdue them so eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblo. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the tribe over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

Today's pottery from Santa Clara is typically either black or red. It is usually highly polished and designs might be deeply carved or etched ("sgraffito") into the pot's surface. The water serpent, ("avanyu"), is a traditional design motif of Santa Clara pottery. Another motif comes from the legend that a bear helped the people find water during a drought. The bear paw has appeared on their pottery ever since.

One of the reasons for the distinction this pueblo has received is because of the evolving artistry the potters have brought to the craft. Not only did this pueblo produce excellent black and redware, several notable innovations helped move pottery from the realm of utilitarian vessels into the domain of art. Different styles of polychrome redware emerged in the 1920's-1930's. In the early 1960's experiments with stone inlay, incising and double firing began. Modern potters have also extended the tradition with unusual shapes, slips and designs, illustrating what one Santa Clara potter said: "At Santa Clara, being non-traditional is the tradition." (This refers strictly to artistic expression; the method of creating pottery remains traditional).

Santa Clara Pueblo is home to a number of famous pottery families: Tafoya, Baca, Gutierrez, Naranjo, Suazo, Chavarria, Garcia, Vigil, Tapia - to name a few.

Santa Clara Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Koshares

Most Pueblos

Margaret and Luther Gutierrez

Santa Clara

Lois Gutierrez

Santa Clara

Emma Lewis

Acoma

Among the religious figures in Pueblo societies is an order of "sacred clowns," also known as Chiffoneti. Among the Hopi they are a group of five distinct figures known collectively as Payakyamu. They are also known as Kossa in the Tewa language, Koshare in the Keres language, Tabosh among the Jemez and Newekwe among the Zunis. The terms are a bit generic as each pueblo has its own unique names and those names will vary according to the kiva (confraternity or secret society) they belong to. Each has a unique role in the community year-round (to invoke rainfall in particular) and perform in the annual spring and summer fertility rites.

Among the Hopi there are 5 clown figures: 4 of which are katsinam (personifications of spirit). The fifth is the Koshare, a figure that came to Hopi country with the Tewas who migrated there in the years after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. When a Hopi dancer dons the mask of a katsina it is believed that the dancer's personality abandons the body and that spirit possesses it.

Among the other Pueblo peoples, the sacred clowns don't wear masks. Instead, they present themselves with black and white horizontal stripes painted on their faces and bodies, paint black circles around their eyes and mouthes, and part their hair down the middle and bind it in two bunches which stand upright on either side of their head and trim those bunches with corn husks.

Their function is to help defuse community tensions by offering their own humorous take on their tribe's popular culture, by communicating tribal traditions and by reinforcing tribal taboos.

European courts often used to have a "jester" who offered similarly meaningful and humorous social commentary on activities in the court and the kingdom. Juan Suni was a Hopi Koshare who performed his duties one day in 1656 by impersonating the resident Franciscan priest at Awatovi. He continued living life as a Koshare as he journeyed from Hopi country to Santa Fe, where he was arrested and put on trial in 1659. The Spaniards recounted a number of "offenses" Juan performed on his journey and they sentenced him to 20 years of slavery for his actions. 40 years later, the Hopis destroyed Awatovi, burning the pueblo, tearing down the walls and killing all the residents: Awatovi at the time was the largest pueblo in Hopi country (although most residents seem to have spoken Towa) and was also the site of the only Spanish mission in all of Hopiland.

Gutierrez Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Jose Domingo Gutierrez (1844-before 1931) and Tonita Gutierrez (1859-aft 1934)

- Lela (1895-1966) & Van (Evangelio) Gutierrez (1885-1956)

- Luther Gutierrez (1911-1987) & Lupita Naranjo

- Paul & Dorothy (Navajo) Gutierrez

- Gary Gutierrez

- Paul Gutierrez Jr. (1966-)

- Pauline Gutierrez Naranjo (1931-)

- Stephanie Naranjo (1960-)

- Paul & Dorothy (Navajo) Gutierrez

- Margaret Rose Gutierrez (1936-2018)

- Luther Gutierrez (1911-1987) & Lupita Naranjo

- Leocadia Gutierrez (c. 1877-1950) & Thomas Sublette Dozier (Anglo from Missouri) (1857-1925)

- Severa Gutierrez Tafoya (1890-1973) and Cleto Tafoya

- Angela Tafoya Baca (1927-2014) & Antonio Baca

- Alvin Baca (1966-)

- Daryl Baca (1961-)

- David Baca (1951-)

- Leona Baca (1958-)

- Epimenia (Mela) Tafoya (1920-1962) & Robert Nichols

- Robert Cleto Nichols (1961-) & Miana Pablito (Zuni)

- Lydia Tafoya (1923-1975) & Santiago Garcia (San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh)

- Greg Garcia (1961-2010)

- Tina Garcia (1957-2005)

- Virginia Garcia (1963-)

- Maria (Mary Agnes) Tafoya (1925-1983) & Mosimino Tafoya

- Stephanie Tafoya Fuentes (1963-) & Lorenzo Fuentes

- Alita Povijua (1957-)

- Kathy Silva (1947-)

- Gwen Tafoya

- Wanda Tafoya (1950-)

- Eric Tafoya (1969-)

- Lawrence Tafoya (1968-)

- Mary Agnes Talache (1981-)

- Charlene Victoria Talache (1986-)

- Tonita (1930-) & Paul Tafoya

- Paul Speckled Rock (1952-2017)

- Adam Speckled Rock (1972-)

- Kenneth Tafoya (1953-)

- Ray Tafoya (1956-1995) & Emily (Suazo) Tafoya

- Jennifer (Tafoya) Moquino (1977-) & Michael Moquino

- Leslie Tafoya

- Paul Speckled Rock (1952-2017)

- Angela Tafoya Baca (1927-2014) & Antonio Baca

Some of the above info is drawn from Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies

Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members and through interminable searches of the Internet.

Copyright © 1998-2024 by